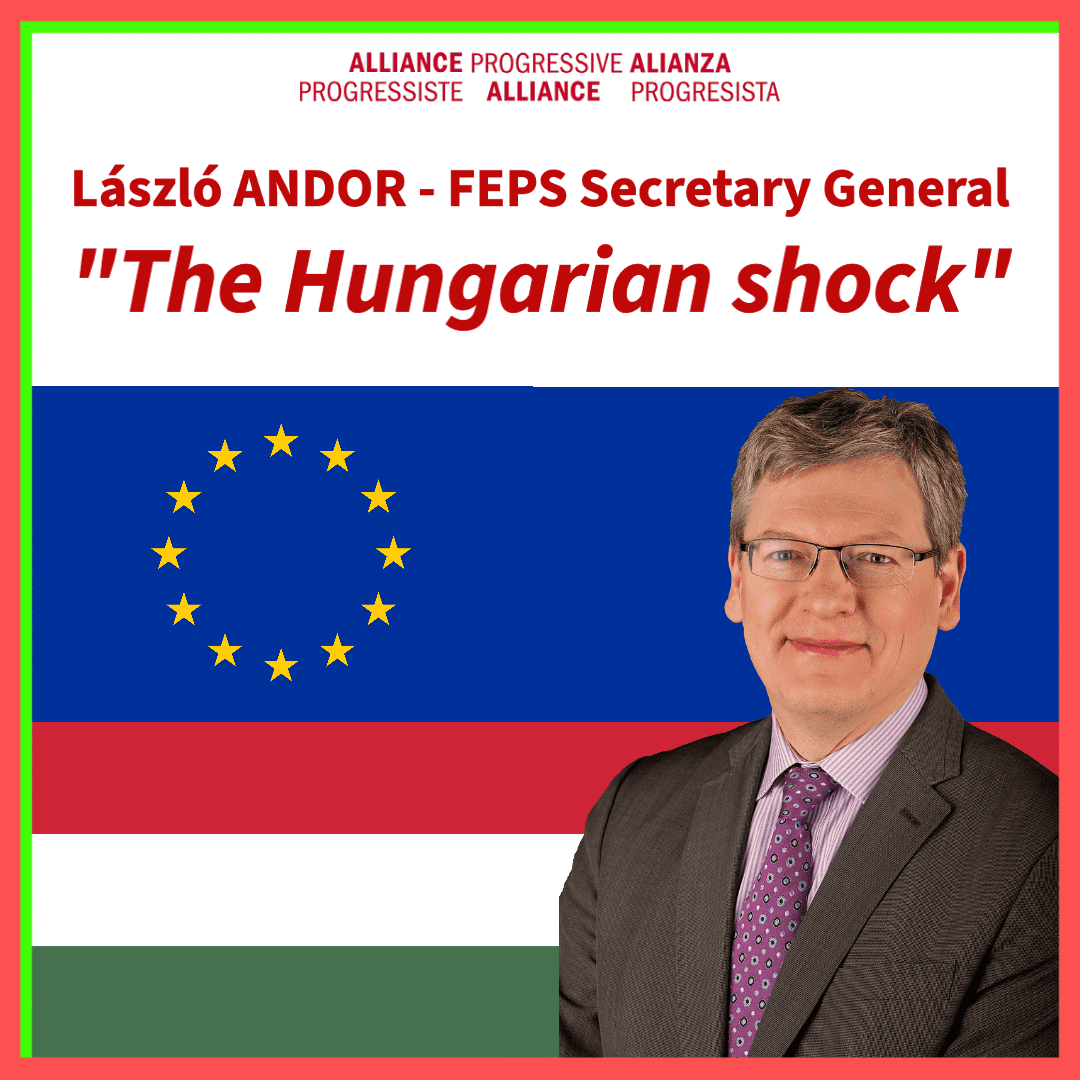

By László Andor, Hungarian and European economist and politician, FEPS* Secretary General

Election outcomes

The likely outcome of the 2022 parliamentary elections in Hungary is that the ruling party Fidesz preserves its supermajority based on a higher vote share than they received in 2018. This runs contrary to the mainstream expectations in previous months pointing to likely Fidesz win but with a strengthened and more united opposition nationwide. And there is stark contrast between this grim situation and the optimism of progressive activists and voters eight months earlier, at the time of the primaries that were organised to select the challenger of Viktor Orbán and the opposition candidates in each and every constituency.

The capital city Budapest is now effectively cut off from rest of the country: in Budapest almost all constituencies were won by opposition while in rest of the country almost all were won by Fidesz. Participation over 75% would have given chance to the democratic opposition (a six-party alliance) to defeat Fidesz nationwide, but such high activity has never happened since 1990. It stopped just below 70 % in 2022, which basically is the same level as in 2018.

According to surveys, the young generation (new entrants to the political market) overwhelmingly supported change. However, there were many voters who had supported one or another participant of the six-party alliance but now decided otherwise. This particularly applies to the formerly far-right Jobbik party, from which the majority of the earlier supporters deserted to back either Fidesz, or the newly organised far right “Our Homeland Party”, or just stayed at home.

It has to be highlighted that the Fidesz campaign budget has been several times greater than opposition budget, exceeding also legal limit. This made a big difference in advertising, social media appearances and other ways. Even one of the bogus parties (MEMO, launched by a porn tycoon shortly after the opposition primaries) was in better financial condition than the united democratic opposition. Fidesz in previous years undermined the finances of opposition parties, including through arbitrary fines from the Court of Auditors.

Hungarian elections have been free but not fair ever since 2014, given the many distortions built into the system and institutionalised bias (just 5 min air time for opposition in 4 years in state television, lack of fair voting opportunities for expats, gerrymandered districts, “vote for public work” deals in villages, incentives to bogus parties etc.). OSCE observers also pointed out that there was no clear separation between information campaign by the government and party political advertising by Fidesz.

_______________________________________________________________________

* Foundation of European Progressive Studies

Campaign controversies

Viktor Orbán’s corona performance has been abysmal (one of the highest death rates in Europe, scandalous ventilator procurements, messy vaccine strategy, mistreatment of health care staff and weak social protection) which in normal circumstances would have undermined his electoral chances. However, Orbán campaigned already in 2021 by announcing big financial giveaways like pension bonus, tax relief for youth, minimum wage increase, continuing middle-class family benefits etc. (the timing of these boosted economic feel-good factor ahead of the elections). The effect shows that steadily rising income matters a lot for median voter, and the opposition should have focused much better on cases where the government’s welfare policies actually failed.

The rising inflation since Autumn caused widespread public anxiety and anger but Orbán introduced price caps (first for petrol than for certain basic food products) and gave the impression of being a PM who cares and is ready to fight the evil effectively and protect the Hungarians. These interventions were consistent with Orbán’s decade long regulation of household gas prices, a totemic issue in Hungarian politics.

It should also be highlighted that the 2022 parliamentary election was linked to a referendum on LGBTQI issues organised on the same day, which had a “Pavlovian” effect: social conservative voters were less likely to make mistake with a list of questions in their hand. This referendum—which eventually became inconclusive—makes little difference in school practices on LGBTQI issues but the year-long campaign on sexual differences scapegoats the affected community and puts them in risk.

This was not the first time when Fidesz managed to turn parliamentary election into a kind of referendum, with simple messages. In 2014 the general election was focused on household energy prices, in 2018 on migration, and in 2022 on LGBTI issues and the Ukraine war. Meanwhile, the opposition campaign has been somewhat messy, despite the successful primary in 2021 Autumn.

The main inconsistency on the side of six-party opposition has been that a mainly centre-left voting base was served with a (modern) conservative Spitzenkandidat. Non-partisan Péter Márki-Zay won the primaries thanks to the centre-left division and his capacity to mobilise youth support, but subsequently failed on tactics as well as policy, despite great energy put in the campaign.

The opposition’s narrow focus on gigantic Fidesz corruption and Orbán’s alliance with Russian President Vladimir Putin energised existing voters but failed to bring many new ones (since these issues appear to be less relevant for ordinary people than material gains). The European Union failed to call out Orbán on corruption even if abuse of EU funds has been industrial scale, and presenting outrageous cases did not result in the slightest erosion of the Fidesz camp.

The Russian question

The war between Russia and Ukraine made a big effect on the Hungarian campaign in the last five weeks and turned out to be decisive factor. Orbán successfully played the “peace card” and the pro-government media regularly called the opposition “pro war”. For many ordinary voters, the understanding was that “Orbán will keep us out of this war while Márki-Zay would drag us into it” and this was a crucial argument.

Western observers might be perplexed how can someone so close to Putin, like Orbán, paint himself to be a man of peace? Why Hungarians, with the memory of 1956, do not react stronger against the invasion and show more solidarity with Ukraine? With a closer look at Hungarian history and society, this is not so difficult to understand. No doubt, the Soviet military intervention to suppress the Hungarian uprising in 1956 was brutal, but the assumption that all further developments would be determined by this dark chapter is wrong and delusional. Hungarians had several heroic uprisings in history and 1956 is one of those. But “golden ages” in Hungarian history were usually linked to compromise with colonial powers (late 19th century and the 1960s—70s).

One can draw a parallel between Hungarian and Ukrainian history but this has not much to do with 1956. Russia acquired much of the present time Ukrainian territory in the 18th century, just as the Habsburg Empire annexed Hungary fully in the 18th century. In both cases the acquisition of territory took place at the expense of the Ottoman Empire which at that time was in decline. Hungarians fought the Austrians for independence (especially in 1848-9) in vain, but the best time for economic and political development for Hungary came after the famous compromise with the Austrians in 1867.

The 1848-9 uprising of Hungarians against Austrians was eventually put down by the Russian army which came to the rescue of the Habsburg Empire fulfilling a commitment they had made in 1814. In 1956 the Soviet Union invoked the Warsaw Pact that had been signed one year earlier. The intervention of the Soviet army in 1956 cost over 2000 lives and the repression that followed was severe (over 200 people executed). But from the early 1960s Hungarians experienced “goulash communism”. For many who grew up in those times the constantly improving living standards are more important than which army is stationed in the country.

If you ask Hungarians what the greatest tragedies for us were (in 20th century), more right wing people would say the outcome of World War One (including Trianon) and more left wing people would say the outcome of World War Two (including the Holocaust). In first France and in second Germany is implicated. 1956 does not come near in either case what concers the number of victims or further implications. The memory of 1956 hurts Hungarians but it rarely mobilised large numbers in the last 30 years when celebrating the anti-Soviet uprising has been free. Maybe most Hungarians don’t particularly like Russians but they put things into perspective and value the opportunities of peaceful and pragmatic cooperation.

Hungarian nationalist views are attached to the notion that the West “gave us” to the Russians at the Yalta Conference (1945). Linked to this is the point that in 1956 the West (US, Radio Free Europe etc.) encouraged but did not support the armed uprising of Hungarians against the Soviet intervention. This is being compared to current Ukrainian situation. Adding the concerns of ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine who felt culturally oppresed at the time of rising Ukrainian nationalism, it is not so hard to understand why the complains about Putin fell flat at the time of the recent election campaign and why most Hungarians prefer to stay away from the war of two great Slavic nations.

![Headline: Hier bitte das Thema [ Headline] 24.10.25, Lucerne, Switzerland, Progressive Alliance PA women conference](https://progressive-alliance.info/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/MAW251024mw859033AdobeRGB-scaled-recq0qxu9kb6pncdi2i7wo6ttne03ppnu58zxxdc74.jpg)